HOME | QUICK START | IN DEPTH | ABOUT ME | ABOUT APP

In Depth Tutorial on Using GridTracks

Inventory and Sales

Keeping track of both your inventory expenses and sales are important for keeping track of how money enters and leaves your business. The sections below will show you how to use double-entry bookkeeping to do this.

Inventory

If your business sells items, it is important to keep track of inventory to better see where your money is going. Every once in a while, you must also do a physical count of all inventory to see where you are at. There are computerized systems that can automate this process, but unfortunately GridTracks does not offer this.

Note that keeping track of inventory will require both asset accounts and expense accounts. For the actual logging of sales, that will be discussed in the next section.

When you first purchase inventory goods, it becomes an asset. You can pay for this asset by crediting assets (thus decreasing total assets) or liabilities (increasing what you owe).

Here, bottled water inventory (asset) is bought using money from our bank account (asset).

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Inventory - Water Botles (1060) | 150.00 | |

| Bank (1010) | 150.00 | ||

| Bought 150 water bottles at $1.00 each. |

Note that if your business is one that takes raw products and manufacturers on them, inventory can be transferred from asset account to asset account. For example, if the business purchased raw wood and then processed it, you would move the inventory from the Raw Wood account to the Processed Wood account

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Inventory - Processed Wood (1080) | 200.00 | |

| Inventory - Raw Wood (1070) | 200.00 | ||

| Processed $150.00 worth of raw wood. |

Finally, at the time that you sell your inventory, it gets logged in as an expense. You can consolidate all sold inventory into one journal transaction if you please. Note that the profit earned from sales will have to be put in another journal transaction.

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Cost of Goods Sold (5040) | 100.00 | |

| Inventory - Water Bottles (1060) | 100.00 | ||

| Sold 100 water bottles for the week. |

Now comes the question of how to determine the cost per good sold. You may first think this is fairly straightforward but an issue arises when you buy inventory over a long period of time. This is because during this period, the price of which you by the goods may vary (it may go up or down), particularly due to inflation.

In double-entry bookkeeping, there are two methods of keeping track of the cost of goods sold due to fluxuations in purchase price. Imagine that I have purchased 2,000 bottles of water over the course of one month at varying prices, as described in the table below:

| Purchase Date | Price Per Unit | Amount Purchased | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jun 10 | $1.00 | 1,000 | $1,000.00 |

| Jun 20 | $1.15 | 500 | $575.00 |

| Jun 30 | $1.20 | 500 | $600.00 |

| Total | 2,000 | $2,175.00 |

Note that over the course of the month, 2,000 bottles were bought for a total inventory amount of $2,175.00. Since the bottles were bought at different prices, this poses a problem as to how we would determine the Cost of Goods Sold for just one bottle of water.

Given the data above, you can either choose to use FIFO (First-In, First-Out) or Weighted Average Cost to determine the value to added to Cost of Goods Sold per bottle of water sold.

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| FIFO (First-In, First-Out) |

FIFO means what it is called. Basically when you sell a good, Cost of Goods Sold is based off the price of the product that was purchased first. For instance, from the example above, because the first 1,000 bottles of water were bought at $1.00/bottle, the first 1,000 bottles sold would create a total Cost of Goods Sold at $1,000. At this point, the first 1,000 bottles of water are sold and now out of inventory, the price of the product purchased first is now $1.15/bottle, and so for the next 500 bottles sold, the cost of goods sold for one bottle is $1.15, reaching a total of $575.00, before we have to take into consideration the bottles that were bought at $1.20. At this point, each subsequent bottle will log a cost of goods sold per bottle at the purchase price of $1.20, up to a total of $600.00 for all 500 bottles bought and sold. Note that if initially 1,250 bottles were sold at the beginning, than the first 1,000 bottles would create a Cost of Goods Sold expense at $1.00/bottle, while the next 250 bottles will be sold at $1.15/bottle. In total, the total amount put into Cost of Goods Sold would be 1000 × $1.00 + 250 × $1.15 = $1,000 + $287.50 = $1,287.50. |

| Weighted Average Cost |

The Weighted Average Cost is based off the average cost of all your inventory. Once the average cost per bottle is calculated, each bottle is logged into Cost of Goods Sold at this average price/bottle. Please note that this is a weighted average. If you took just the average of the three prices, or ($1.00 + $1.15 + $1.20) ÷ 3 ≈ $1.12, this would be incorrect. The problem is that there are double the amount of bottles bought at $1.00 (1,000 bought) versus those bought at either $1.15 or $1.20 (500 bottles bought for each). The algorithm for finding the weighted average cost is: [(price per item) × (quantity bought) + (price per next item) × (next quantity bought) + …] ÷ (total items bought) In the example, the weighted average cost would be: [$1.00 × 1,000 + $1.15 × 500 + $1.20 × 500] ÷ 2,000 = [$1,000.00 + $575.00 + $600.00] ÷ 2,000 = [$2,175.00] ÷ 2,000 ≈ $1.09/bottle This means that for every bottle sold, you would set the cost of goods sold to $1.09/bottle. Of course, if you have sold some bottles and bought more, you would have to recalculate the subsequent weighted average of all the cost of goods you currently have in inventory. So, in the case above, if you were to have sold 1,250 bottles of water, the cost of goods sold from this transaction would be: $1.09 × 1,250 = $1,362.50 |

Please note that if you wish to keep track of inventory using GridTracks, by clicking on this button in the General Ledger will take to you a textbox for that account, where you can add the information as you please.

Dealing with Sales

When you make a sale, you can either get paid immediately by cash, or on credit in the form of Accounts Receivable. If you accept credit in Accounts Receivable as payment, then it is your responsbility for loss if the customer refuses to pay down the line. Credit cards are considered cash payments since you get the money immediately—it is up to the bank to chase down the customer if they do not pay their bill.

Below is a typical journal transaction for a sale. Here Taxes Payable is a liabiliy account. This is because while the money the customer spends on taxes is put into the bank, it is not money that you own. Thus, the liability is referencing that you "owe" this money to the government, and it is just temporarily in your bank account at the moment.

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Bank (1010) | 810.00 | |

| Water Bottle Sales (2085) | 800.00 | ||

| Taxes Payable (2050) | 10.00 | ||

| Sales from water bottles for the week. |

Note here that Bank is an asset, Water Bottle Sales a revenue account, and Taxes Payable a liability account.

Of course if you were to charge the sale on credit, than it would be the same process as above, but instead of the Bank asset, you would utilize one of your Accounts Receivable. Again, it is your responsibilty to ensure the customer pays—if they do not, then you will incur a loss.

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Accounts Receivable—J. Smith (1040) | 810.00 | |

| Water Bottle Sales (2085) | 800.00 | ||

| Taxes Payable (2050) | 10.00 | ||

| Sales from water bottles for the week. |

Finally, when the customer does pay, just transfer the money from the Accounts Receivable account into your Bank asset (process of moving assets between accounts discussed at beginning of this section).

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Bank (1010) | 810.00 | |

| Accounts Receivable—J. Smith (1040) | 810.00 | ||

| John Smith paid for his water bottles. |

Things do get slighlty more complicated when you involve Volume Discounts or Sales Discounts.

Volume Discounts

These discounts are provided by your business to encourage bulk purchases of certain items. Note that to supplmenet the discount, the discount will go under an expense account called "Volume Discount".By using a separate expense account for volume discounts, it is easy to see how much these discounts are really costing your business.

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Bank (1010) | 798.00 | |

| Volume Discount (5090) | 12.00 | ||

| Water Bottle Sales (2085) | 800.00 | ||

| Taxes Payable (2050) | 10.00 | ||

| Sales from water bottles for the week. |

Notice here that while the sale itself was logged at $800.00, an expense was logged in at $12.00, representing the volume discount for the customer.

Sales Discounts

Just like with volumne discounts, you can offer discounts to customers on Accounts Receivable for paying their bills before the deadline. Please be aware that if your customer consistently do not take advantage of paying early, it may indicate that they are in financial difficulty.

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Accounts Receivable—J. Smith (1040) | 810.00 | |

| Water Bottle Sales (2085) | 800.00 | ||

| Taxes Payable (2050) | 10.00 | ||

| Sales from water bottles for the week. |

Now when the customer pays for the goods/services, the discounted portion will go into the Sales Discount Expense.

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Bank (1010) | 800.00 | |

| Sales Discount Expense (5100) | 10.00 | ||

| Accounts Receivable—J. Smith (1040) | 810.00 | ||

| John Smith paid for his water bottles. |

Sales Returns and Allowances

In order to remain competitive with other businesses, it is usually important for you to allow a return policy for your goods. A Sales Returns expense is debited when a customer returns a product, while Sales Allowances expense is debited when the customer keeps a defective product at a certain markdown price.

Typically, both returns and allowances are put into one expense account, called Sales Returns and Allowances.

If you are giving back cash for the return (or bank asset), you would want to record this journal entry. Note that you will also want to debit Taxes Payable since the purchase is canceled, and you no longer owe this money to the government:

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Sales Returns and Allowances (5100) | 20.00 | |

| Taxes Payable (2100) | 1.50 | ||

| Cash (1000) | 21.50 | ||

| Customer returned book (paid back with cash). |

If you are allowing for the return on Store Credit, you will want to add to the liability account Accounts Payable, to show that you owe this money in goods somewhere down the line. Note that if your business sells gift cards, you would want to credit Accounts Payable as well (while debiting cash, bank, or some other asset).

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Sales Returns and Allowances (5100) | 20.00 | |

| Taxes Payable (2100) | 1.50 | ||

| Accounts Payable (2075) | 21.50 | ||

| Customer returned book (paid back with store credit). |

Finally, if the customer has paid on credit using Accounts Receivable, you will need to credit to Accounts Receivable (since you are decreasing what he/she owes you).

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Sales Returns and Allowances (5100) | 20.00 | |

| Taxes Payable (2100) | 1.50 | ||

| Accounts Receivable—J. Smith (1075) | 21.50 | ||

| Customer returned book (canceled purchase on credit). |

Note that for Sales Allowances, you would use the same entries as above, but you just would debit the discounted amount lost to Sales Returns and Allowances.

If you are doing a sales return with a product that can be resold, you will need to update inventory and Cost of Goods Sold:

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 15 | Inventory—Books (1060) | 20.00 | |

| Cost of Goods Sold (5001) | 21.50 | ||

| Customer returned book — returned to inventory. |

Here, the cost of goods sold was credited, lowering this expense, and inventory is debited, as you have added the product back to the inventory stock.

Sales from Services

Things become slightly different when you business revolves around selling services and not inventory goods.

When you are providing a service over time, you should log in revenue at ceratin periods. For example, if you charged $600.00 for a task that will take a whole month, you may decide to log in $150.00 per week into revenue.

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 22 | Accounts Receivable—J. Smith (1070) | 150.00 | |

| Service Revenue (4085) | 150.00 | ||

| Received revenue for 1 week of service work. |

In the case that you may require a deposit for your services, it is important to keep track of the unearned revenue in a Liability Account, because this is technically unearned. For example, if in the previous example you require a $500.00 deposit, it would go into the General Journal as:

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jul 22 | Accounts Receivable—J. Smith (1070) | 500.00 | |

| Unearned Revenue (2095) | 500.00 | ||

| Recorded deposit needed for service work. |

If say that total bill at the end of the month was $1,500.00, then the Unearned Revenue liability will be converted to Service Revenue, and the rest of the money will also go to Service Revenue.

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aug 22 | Accounts Receivable—J. Smith (1070) | 1,000.00 | |

| Unearned Revenue (4095) | 500.00 | ||

| Service Revenue (4085) | 1,500.00 | ||

| Completed Service. |

Allowance for Doubtful Accounts

When you offer products to customers on credit, you run into the risk of them not being able to pay you back. The issue here is that when you record the purchase into Accounts Receivable, you are overestimating your profits. Instead, you use an account called Allowance for Doubtful Accounts, which acts against Accounts Receivable to account for this risk, top avoid this. Note that typically in the first year of running your business, you can leave Allowance for Doubtful Accounts blank.

Allowance for Doubtful Accounts is called a contra-asset account, because it is an asset that acts again Accounts Receivable (with a credit balance). Its job is to decrease profits due to estimation of Accounts Receivable that will not be paid back.

Once you have run your business for about a year, it may be time to start using Allowance for Doubtful Accounts.

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aug 22 | Bad Debt Expense (5900) | 1,000.00 | |

| Allowance for Doubtful Accounts (1900) | 1,000.00 | ||

| Believe that $1000.00 won't be paid back from Accounts Receivable. |

Note that the amount set to Bad Debt Expense is used to offset Allowance for Doubtful Accounts. The Bad Debt Expense contains the amount you believe will not be paid back from Accounts Receivable, while Allowance for Doubtful Accounts will decrease total Accounts Receivable in lieu of this.

For more information about predicting Bad Debt Expense, see the Finalizing Data section.

When you finally choose to decide to write off the purchase, you will write off the Accounts Receivable using Allowance for Douftful Accounts, as seen below:

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aug 22 | Allowance for Doubtful Accounts (1900) | 500.00 | |

| Taxes Payable (2155) | 10.00 | ||

| Accounts Receivable—J. Smith (1150) | 510.00 | ||

| Had to write off purchase from J. Smith. |

If somewhere down the line the customer ends up paying he or her bill, then you will reverse the transaction seen above (note that you will have to pay taxes again on this purchase):

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aug 22 | Accounts Receivable—J. Smith (1150) | 510.00 | |

| Taxes Payable (2155) | 10.00 | ||

| Allowance for Doubtful Accounts (1900) | 500.00 | ||

| J. Smith ended up paying his bill. |

Finally, becuase the money was paid to you, you can now convert Accounts Receivable into Cash:

| Date | Post | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aug 22 | Bank (1010) | 500.00 | |

| Accounts Receivable—J. Smith (1150) | 500.00 | ||

| J. Smith paid his bill. |

Note here that crediting of Accounts Receivable implies a loss in asset value, which is then transferred onto the Allowance for Doubtful Accounts expense. When this happens, you no longer have to pay taxes on the purchase, and thus that is debited as well.

Cash Sales Receipt

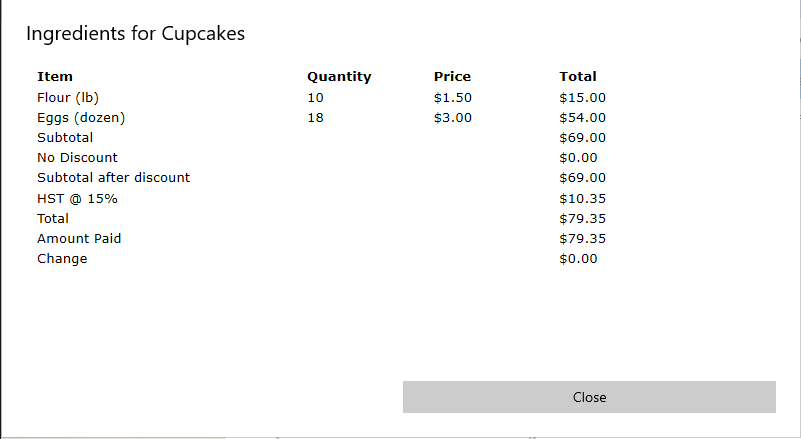

If you wish to add more information to a journal transaction with respect to sales and inventory, you can add a Cash Sales Receipt to a transaction.

When you add or edit a transaction, you have the option of adding a Cash Sales Receipt.

Note that off the bat, you can adjust the title of the receipt, as well as a memo at the bottom for more information.

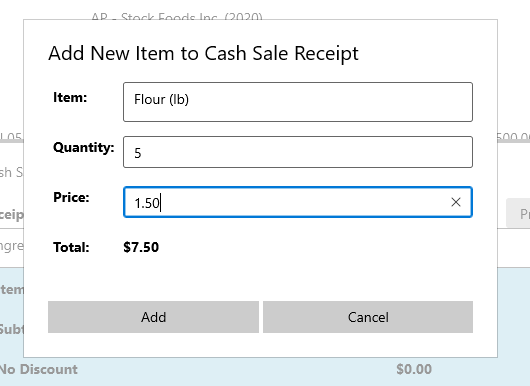

If you hit the (+) button by items, you will be taken to a dialog box where you can add an item/service and its quantities.

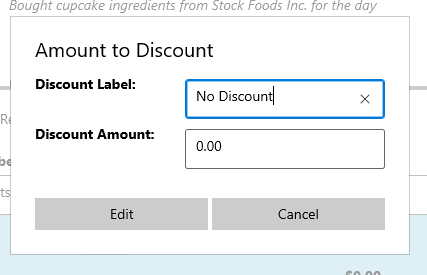

If you click on the Pencil icon by No Discount, you can choose how much to discount by and the title of the discount shown on the receipt (e.g. Volume Discount, Flat-Fee Discount, 15% Discount, etc.)

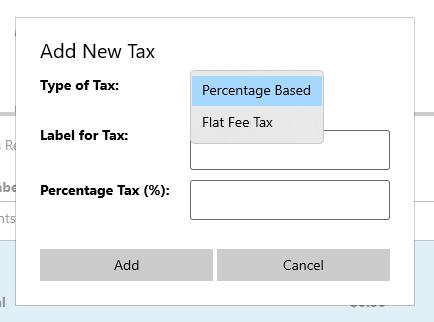

For taxes, you can add multiple, and for each you can choose between percentage based and flat-fee based.

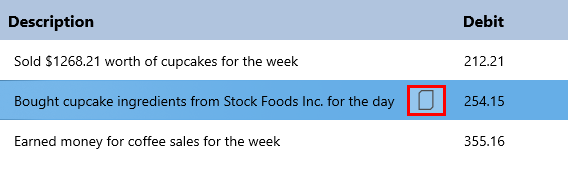

To view your cash sales receipt in either the General Journal or General Ledger:

In the General Journal:

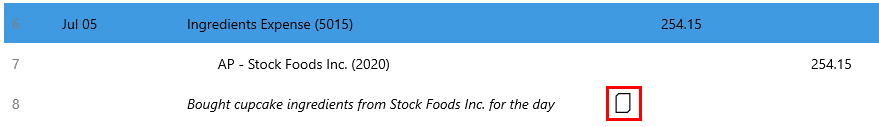

In the General Ledger Accounts View:

Finally, the receipt will look like this when you open it:

Next Steps

- Payroll

- Asset Depreciation

- Paying and Collecting Interest

- Finalizing Data

- Viewing Summary Data (Balance Sheet, Income Statement)

- End-of-Period Preparations

Credits

Please note that most of the information from this site is taken from the book "Bookkeeping for Canadians for dummies" by Lita Epstein and Cécile Laurin.

(Epstein, L., & Laurin, C. (2019). Bookkeeping For Canadians For Dummies. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)